22 Feb ON THIS DAY | The Dalai Lama Enthroned

Ever wondered what one would give to the new Dalai Lama if one had the opportunity to attend his enthronement ceremony?

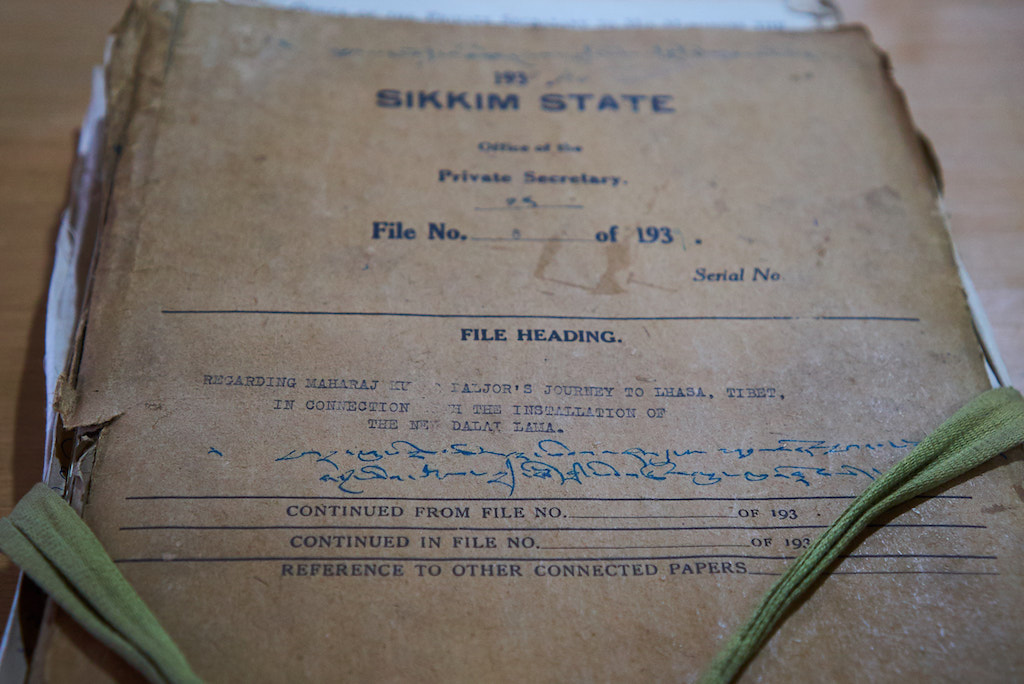

This file (1939-40), over 200 pages long, provides a chronological and detailed account of the planning and sourcing of gifts, articulated concerns and queries about culture, customs, and protocol, and vivid travel descriptions of the journey from Gangtok (Sikkim) to Lhasa (Tibet), for the infant Tenzing Gyatso’s official enthronement as His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama.

Recognised as the official reincarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama in 1939, his enthronement ceremony as the next Dalai Lama was scheduled for 22 February, 1940 in Lhasa, the Tibetan capital. In Sikkim (which had close relations with Tibet, spiritually, culturally, economically, and familial), officials were deciding what gifts to send to Lhasa for the occasion, and who would represent the Sikkim State at this auspicious and once-in-a-lifetime ceremony.

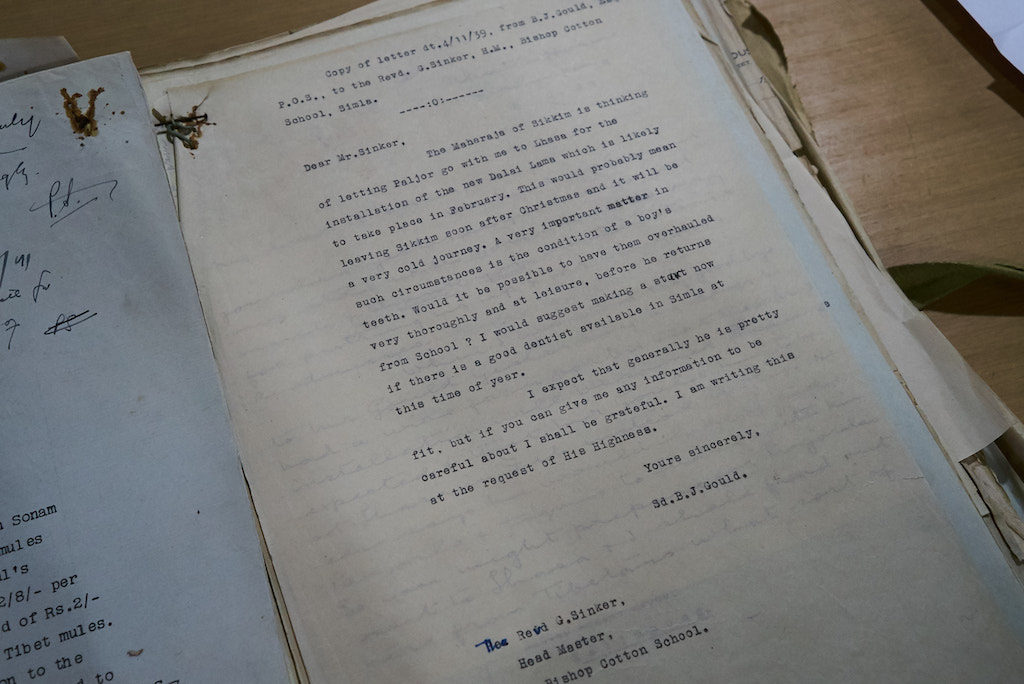

Sikkim’s 11th Chogyal, Tashi Wangyal Namgyal (r.1914-1963), chose to send his eldest son, Crown Prince Kunzang Paljor Namgyal (1921-1941), and the British decided to send Basil Gould (Political Officer, Sikkim), who would have been more familiar with the cultures of the region.

It seems Gould took it upon himself to write to the headmaster of Bishop’s Cotton School (Shimla) where Crown Prince Paljor was studying, informing the school of the Prince’s impending absence – and rather comically, it seems he felt that “…the condition of a boy’s teeth” was a “very important matter”!

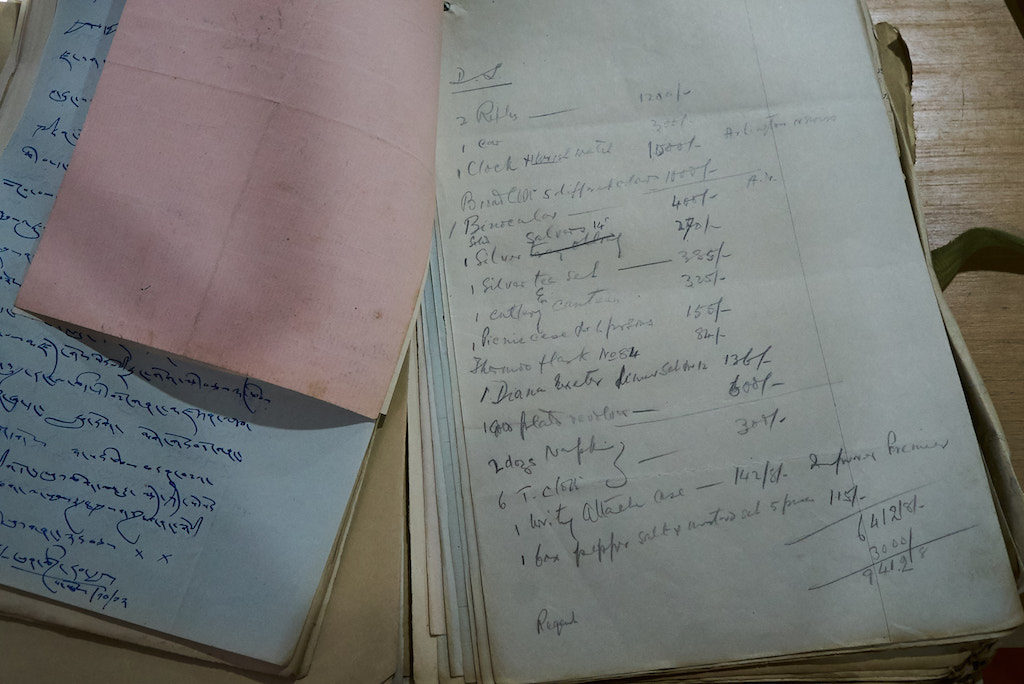

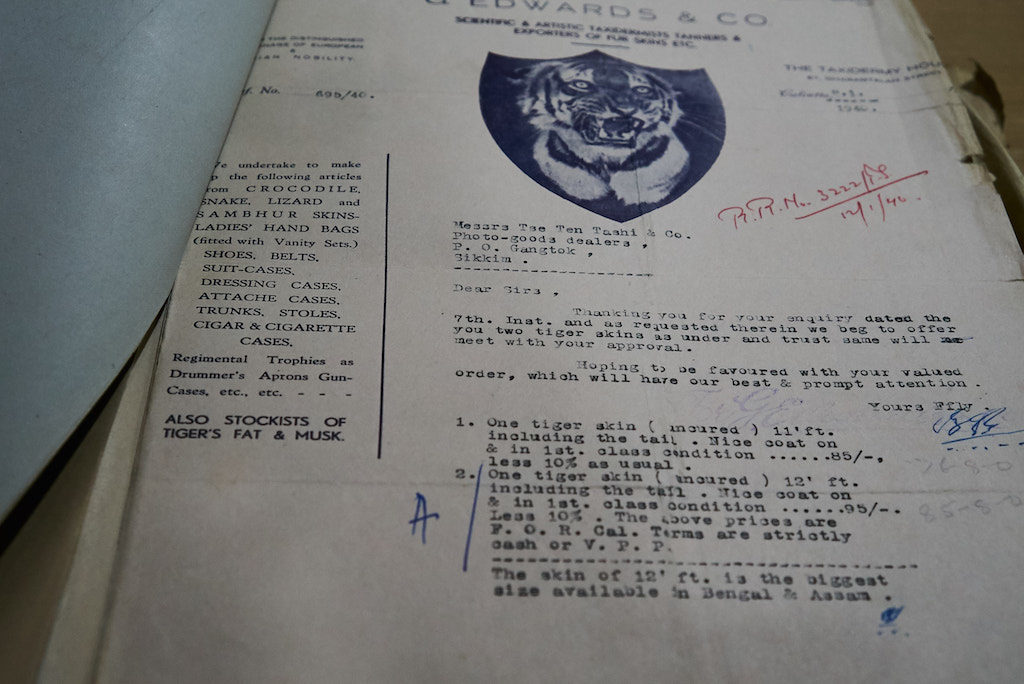

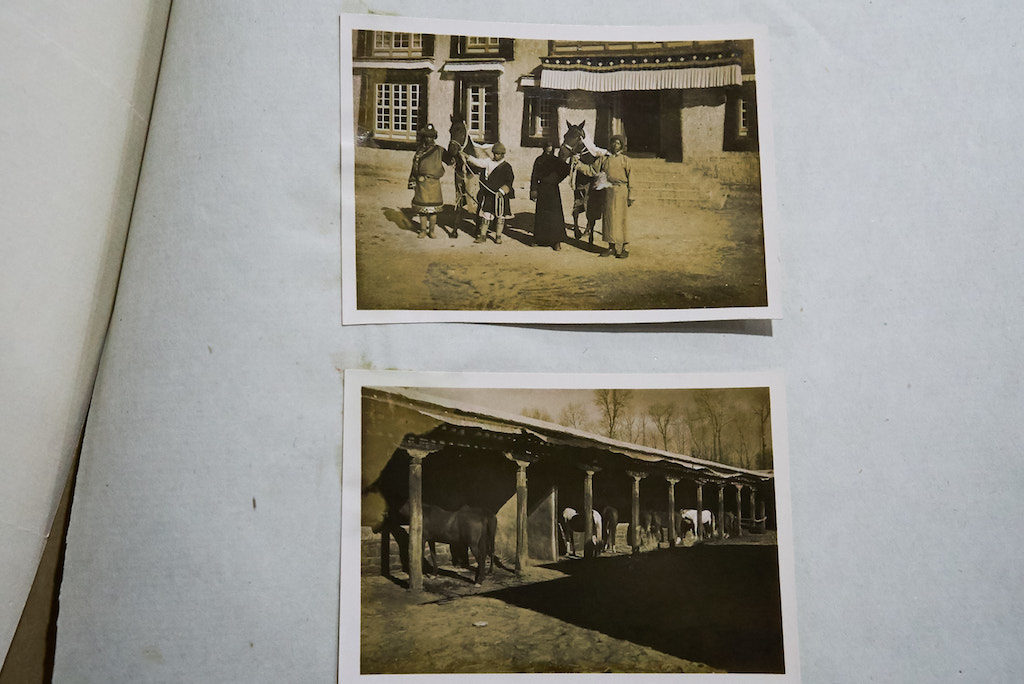

Meanwhile, the Chogyal’s office set to work brainstorming gifts to offer the new Dalai Lama, sourcing them from various vendors from Darjeeling, Kalimpong, and the Army and Navy Store, Calcutta. The gifts included, among other items: A pair of sporting rifles; a 12ft tiger skin; a clock; a writing attaché case, a silver tea set, a pair of binoculars, and a pair of English ponies — the latter evidently caused quite a bit of trouble in their procurement as the file goes on to illustrate!

The Chogyal’s eldest brother, former Crown Prince Tsodag Namgyal (1877-1942) had been removed from the line of succesion by the British in the mid-1890s and had been living in Tibet ever since. His son, Jigme Sumtsen Wangpo Namgyal, was a big support in the Chogyal’s endeavours to pay respects to the Dalai Lama, and it has been interesting to see how little the political interference and geographical borders seem to have affected the strength of family ties.

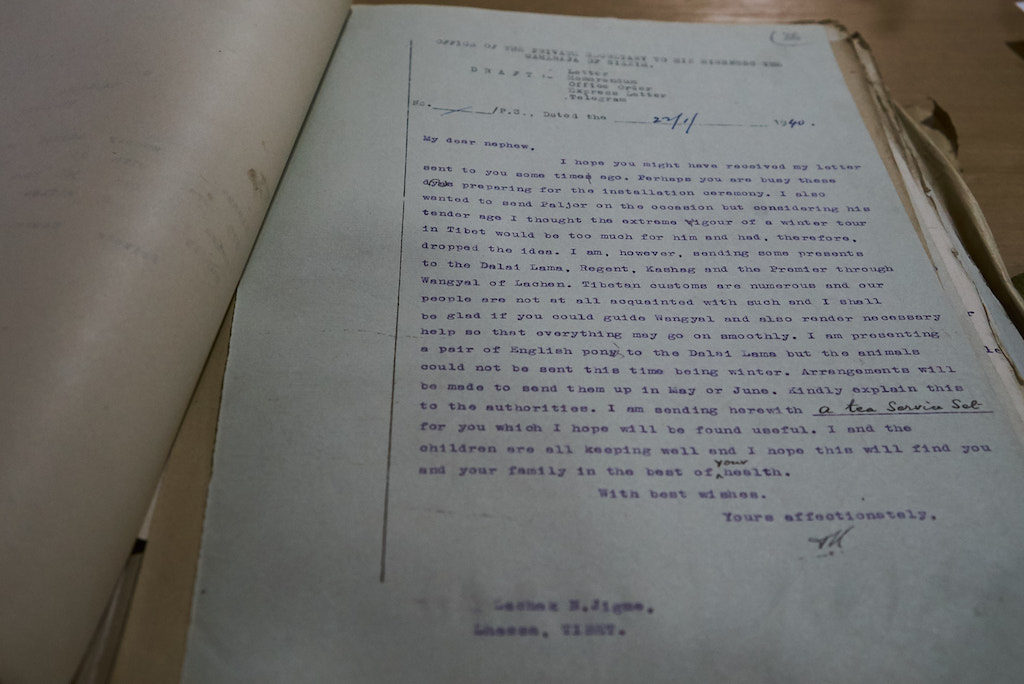

On 22 January, 1940, the Chogyal writes to his nephew, Jigme Sumtsen, to inform him that due to Prince Paljor’s young age and the anticipated harsh winter weather, Sikkim will instead send the Pipon of Lachen1.

The Chogyal asks his nephew to guide Pipon Sonam Wangyal in the elaborate, and oftentimes confusing, protocol of Lhasa aristocracy, and informs him that he is sending a tea set to Jigme Sumtsen in advance, as a token of his appreciation.

On the 24 January, the Pipon sets off for Lhasa with four orderlies and arrives 13 days later on the 6 February, 1940.

Meanwhile, the Chogyal accompanied by Prince Paljor and Princess Pema Tsedeun had left for Delhi to attend the investiture ceremony of the Viceroy of India. On their way back they visited Varanasi and Bodhgaya on Buddhist pilgrimage, and the correspondence between Chogyal and his nephew continued despite the hurdles of distance and difficulty of communication deriving from constant travel in early 20th century India.

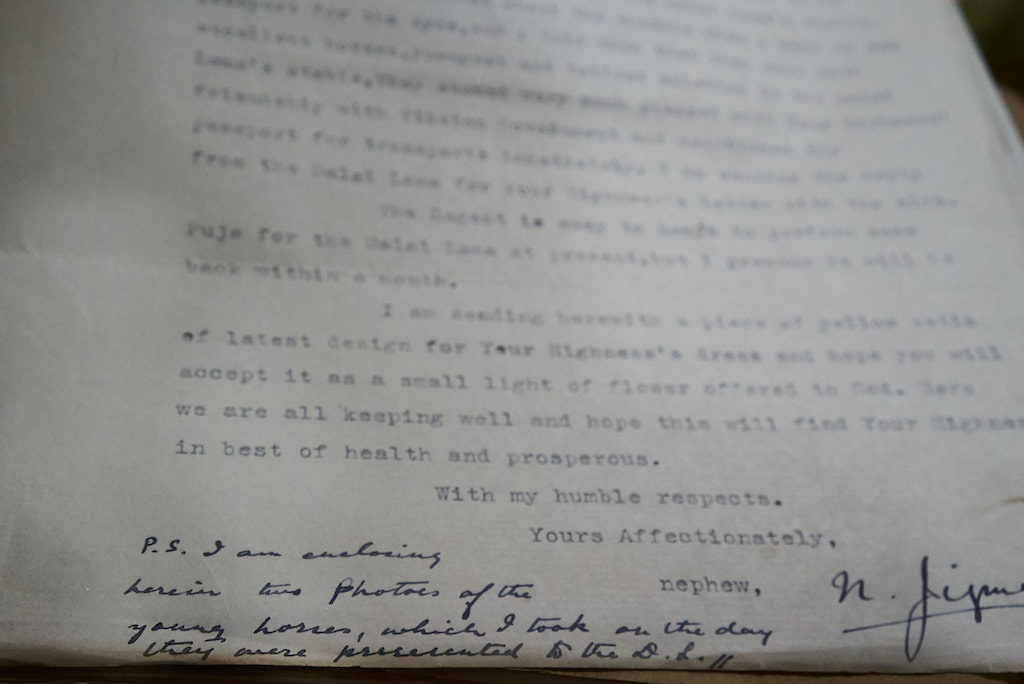

These beautifully articulated, and oftentimes endearing letters, exchanged between uncle and nephew provide windows of insight into both mundane and courtly life of the era. The latter wonderfully illustrated with Jigme Sumtsen reporting to the Chogyal about the ceremony’s success, the reception of the gifts from Sikkim, and reference to the official letters of acknowledgement that are being carried back across the Himalayas by Pipon Wangyal.

But where does one find a pair of English ponies on the Indian subcontinent in 1940? With the start of summer, the search began in earnest, and queries were sent out to Kalimpong, Calcutta, Bombay, and eventually to the Punjab, requesting information on ponies of a certain height and colour.

The Chogyal’s brother-in-law, a Bhutanese known as Raja Sonam Tobgay Dorji (1896-1953) was based in Kalimpong, and he along with Sergul Tsering (Sikkim’s Vetinary Inspector) travelled to Calcutta, where on the 9 September, after visiting various stables across the city, they found a promising young pony at Dum Dum stable. One down!

From there, on the 13 September, the Veterinary Inspector took a 200 rupee advance and continued on to a firm in Punjab which had a reputation of breeding good English horses, and there he was able to procure the second horse for 1,500 Indian rupees.

By early October, the horses were sent up to Lhasa, again with the logistical help and facilitation of Jigme Sumtsen, and presented to the Dalai Lama’s office. Jigme Sumtsen’s letters back to the Chogyal indicate that the officials in Tibet were both impressed and very happy with the horses, and that above and beyond, they were the tallest horses in the stables of the Potala Palace!

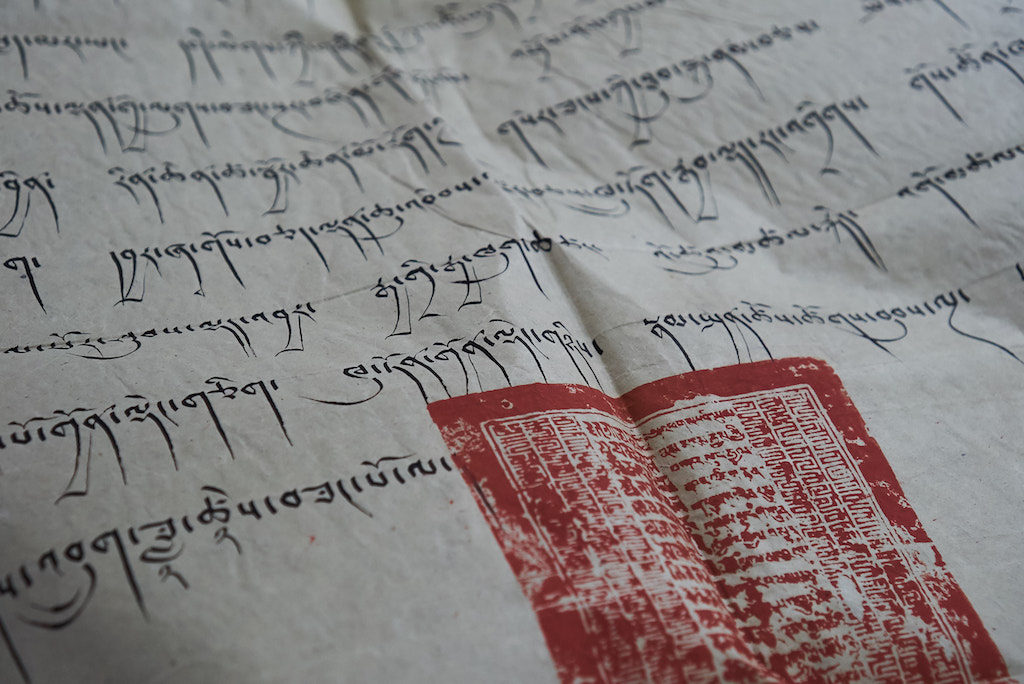

Among other highlights, this file illustrates the frugality of expenditures with meticulous financial accounts of the trip, including the Pipon’s monthly payment (70 rupees; plus 50 rupees for warm clothes); the cost of the travels; and his use of the 50 allocated letter papers, 50 envelopes, 1 pencil, 2 penholders and a pocket book. It includes beautifully written letters from Tibet on handmade parchment paper, and gives insight into the workings of the Sikkim Palace’s administration, as well as the nature of their relationship with both Tibet and the British Empire.

So, if you ever find yourself in a position where you need to present gifts at an enthronement ceremony, this archive might be just what you need…

1. Lachen is a wide valley village in North Sikkim known for its unique system of local community governance, known as the ‘Dzumsa.’ The rotating head of the Dzumsa is refered to by the title ‘Pipon’ (and interestingly, this form of local governance is still practiced today with semi-autonomy within the wider state adminstration).

Originally written for the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme blog

No Comments